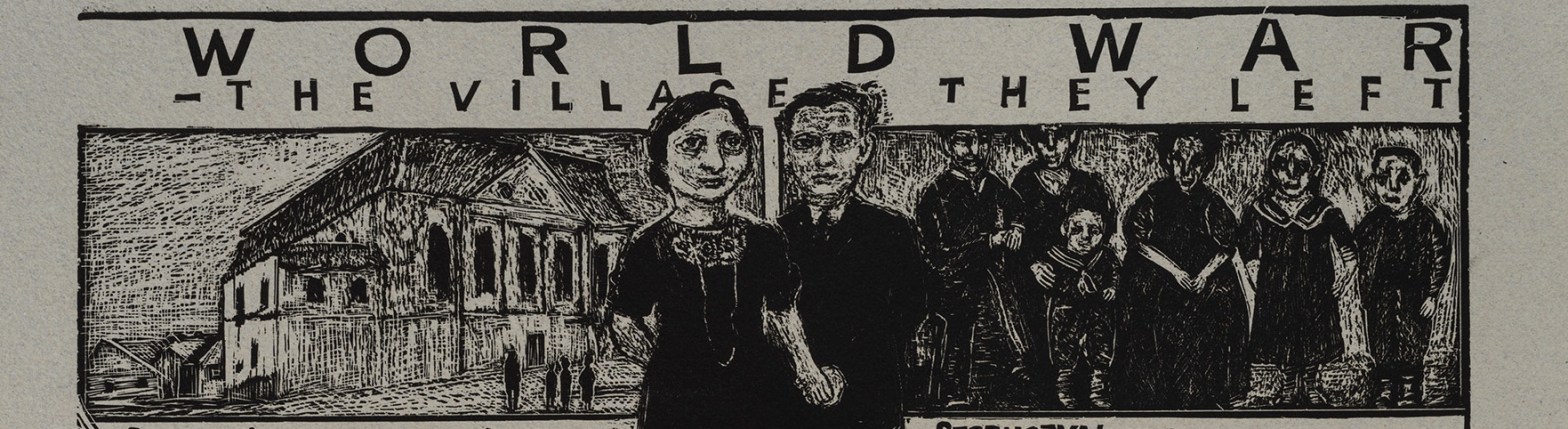

I worked with Frances Jetter when I was art director for the New York Times Op-Ed page (now Opinion) and the New York Times Book Review (still Book Review). She was among a small but influential cohort of satiric graphic commentators whose work appeared influenced by, among others, the early 20th-century German Expressionist social/political critics. Her linocuts had raw, unapologetic power. After leaving the Times, I lost track of her work. But having been gratefully reintroduced through her current graphic “family history,” Amalgam, I remain impressed by her forceful renderings and astute observations and interpretations drawn from life. It is the story of Jetter’s grandparents, who emigrated from a troubled old-world Europe to a disruptive new-world America. It is about union activism at a time when nativism was on the rise. And it is evident where her artistic passions and iconoclastic imagery came from.

We talked about the backstory, the current impact, and the making of this personal and political family saga.

How long have you been working on Amalgam?

It was 12 years in the making, beginning in 2009.

I don’t recall seeing any long-form narrative work from you before. Was this story just waiting to bubble up?

After 25 years of illustrating political articles with linocut prints often completed overnight (which I loved), I wanted to make pictures in series with larger, labor-intensive images.

Still about politics, they increasingly focused on individuals caught up in history.

Amalgam initially started as another artist’s book. Without a set deadline, each 18” x 24” linoleum block, etched with a small cutter, could take several weeks to finish. I’d edition a small number of handmade books with original prints for special collections libraries in universities, the NYPL, and the Library of Congress.

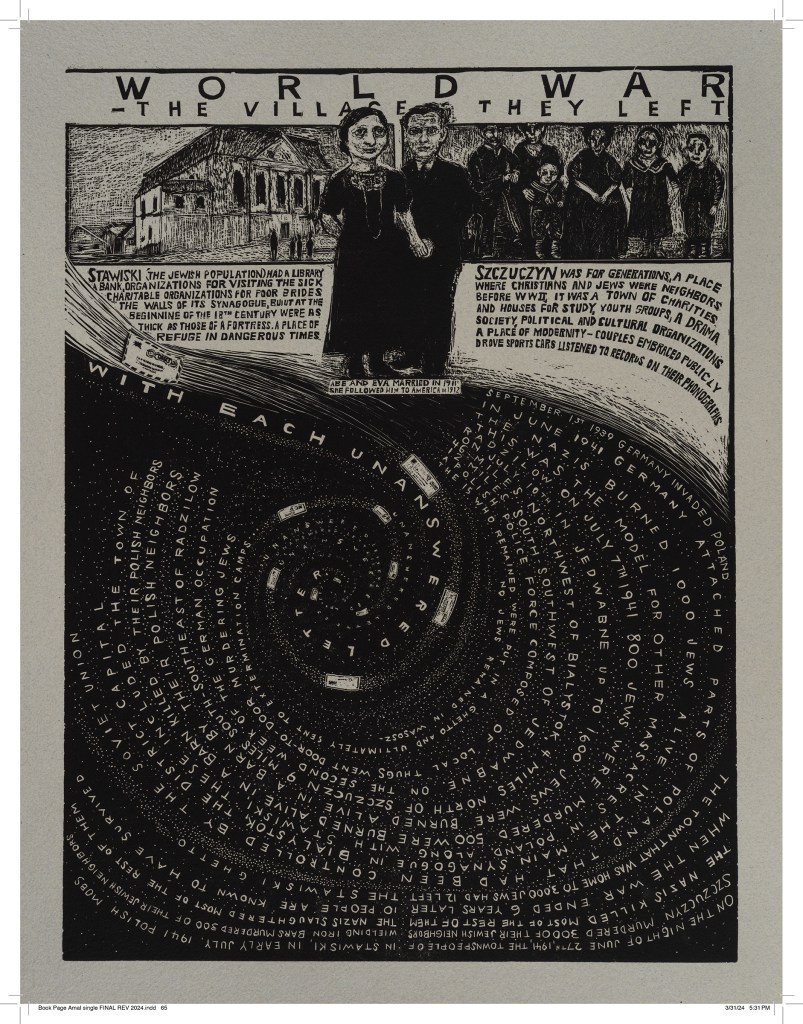

The story involves your grandfather’s escape from Poland and the politics that brought him here.

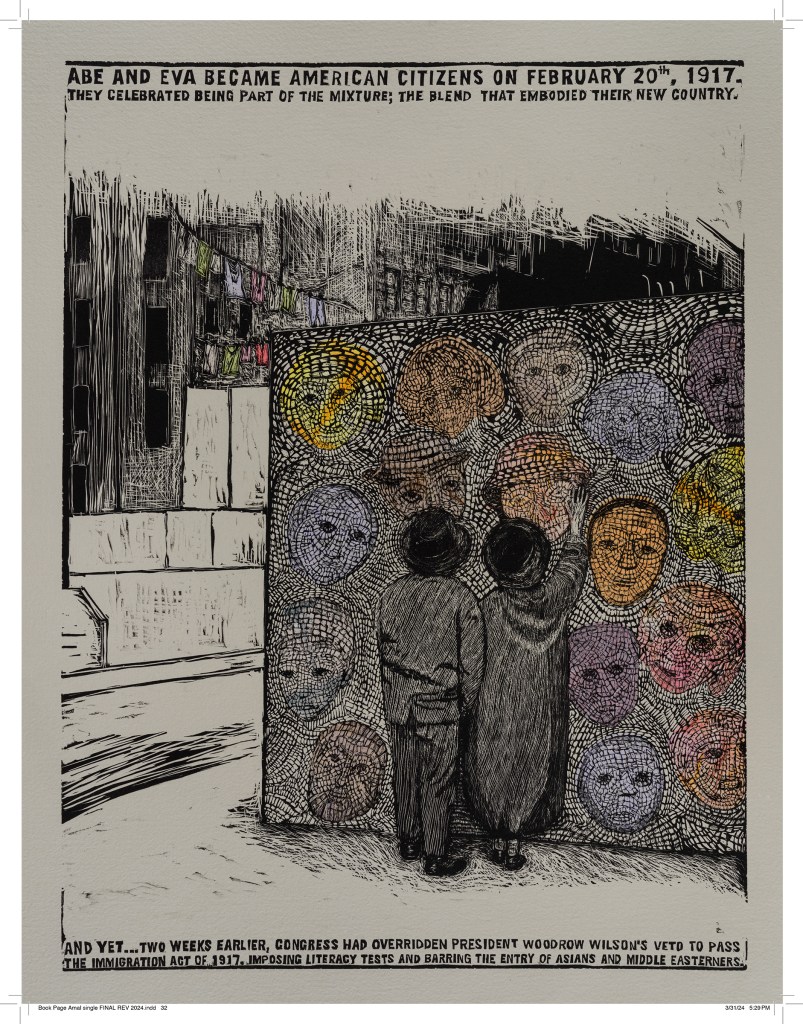

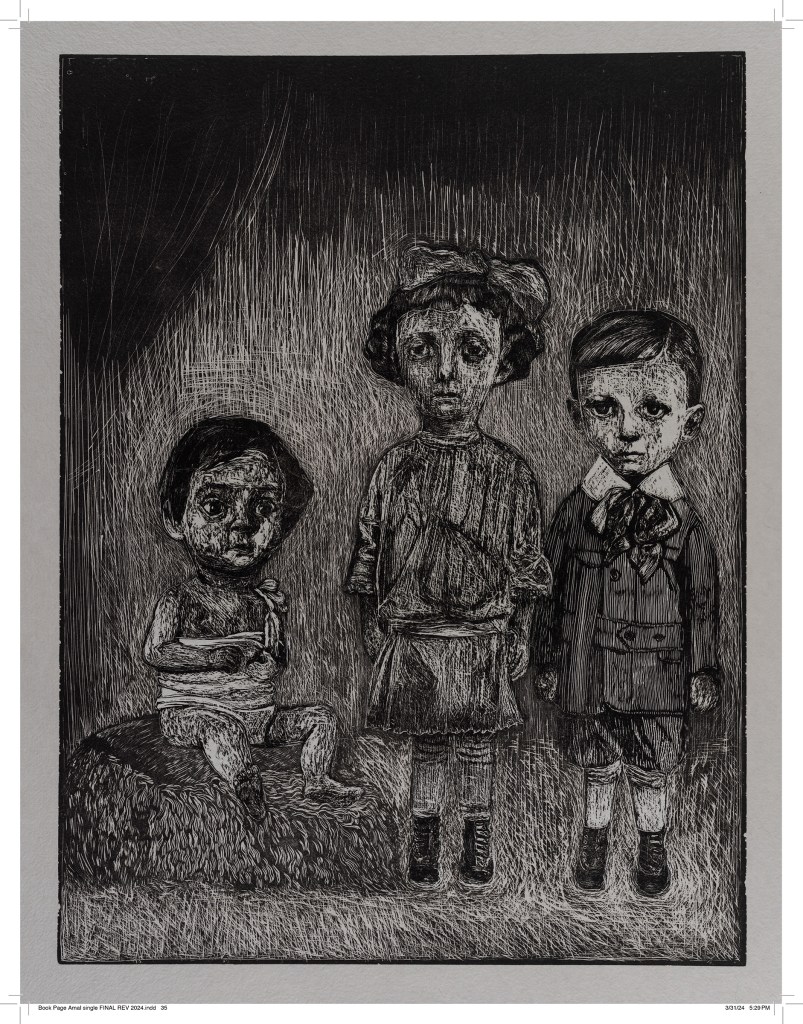

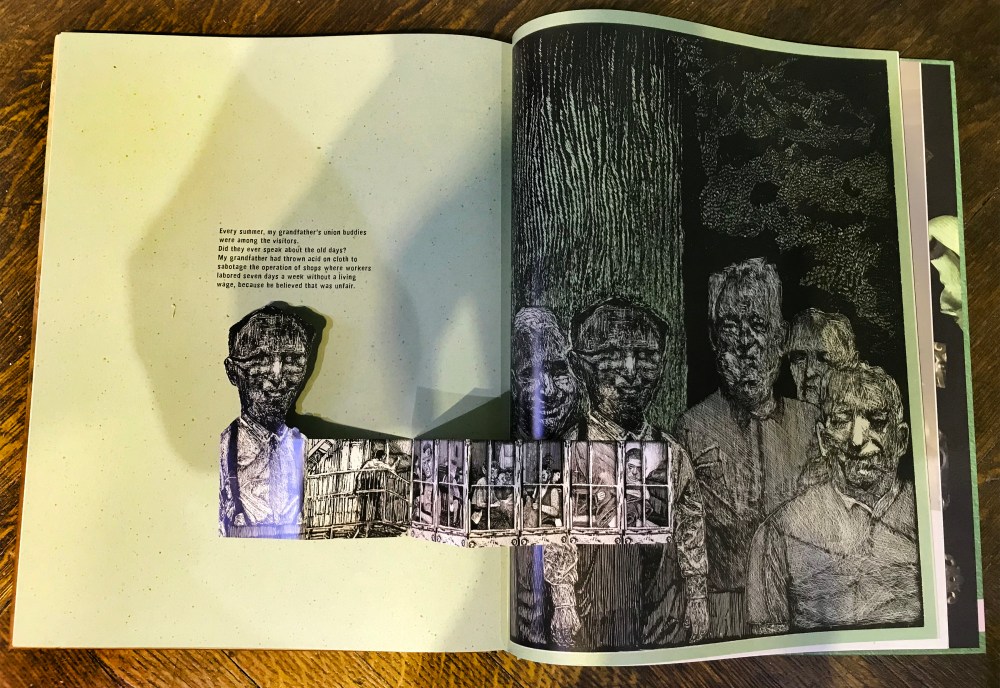

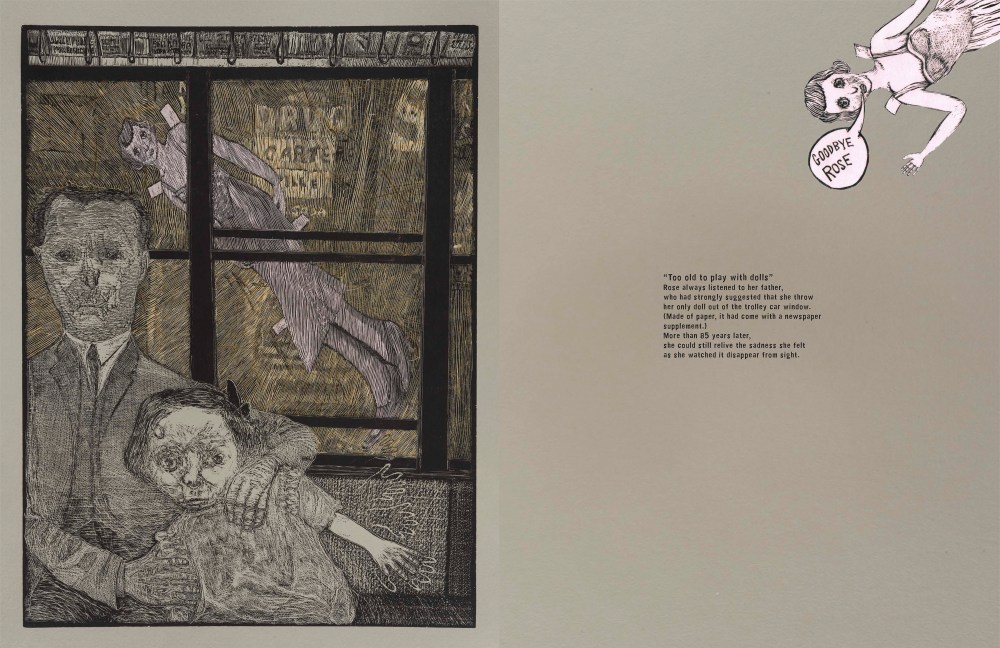

It begins with my grandfather’s 1911 departure from Poland to escape the Russian draft. His job as a pocket maker in a NYC factory precipitated his role as a foot soldier in America’s “Armies of Labor.” The Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, established in 1914, put an end to the 70–80-hour workweek. The union, derived from the word “Amalgam” was a mixture, a blend –“a curious amalgam of the individual and the group” – “a curious amalgam of the pragmatic and the visionary.” The new country, the union, and the family were all “curious amalgams” — mixtures; blends that were sometimes made up of contradictory elements. So my story grew in length and in time. My grandfather was an unyielding patriarch, who believed in freedom in the workplace but never at home. The children weren’t allowed to have toys – books were their only playthings. These images increasingly mixed the personal with the political.

The span of the book reminds me of my own grandparents . . .

The first part of the book ends with the Great Depression and World War II. After the war, factory workers, including those in my family, made the clothing worn by all of America, and because of unions, they became part of an emerging middle class (or as Orwell might have put it, the upper-lower middle class).

This is more than a memoir or family history . . .

That this book is, in part, a memoir was not something I initially considered, but as it kept expanding, this eventually happened — history and aspects of personality are both handed down.

The Epilogue is about the demise of the union, what happened to the family (so many deaths), and to my grandfather’s houses — what continues and what’s changed.

Did you share your work with your grandfather? Given your political leanings, he must’ve been proud.

In 1979, on a visit back to Brooklyn, I showed my grandfather an illustration I’d done for The Nation, about the anti-union tactics of the misleadingly named “National Right to Work Lobby.” He talked proudly of his days as a renegade, climbing up fire escapes, and breaking into shops where workers toiled seven days a week without a living wage.

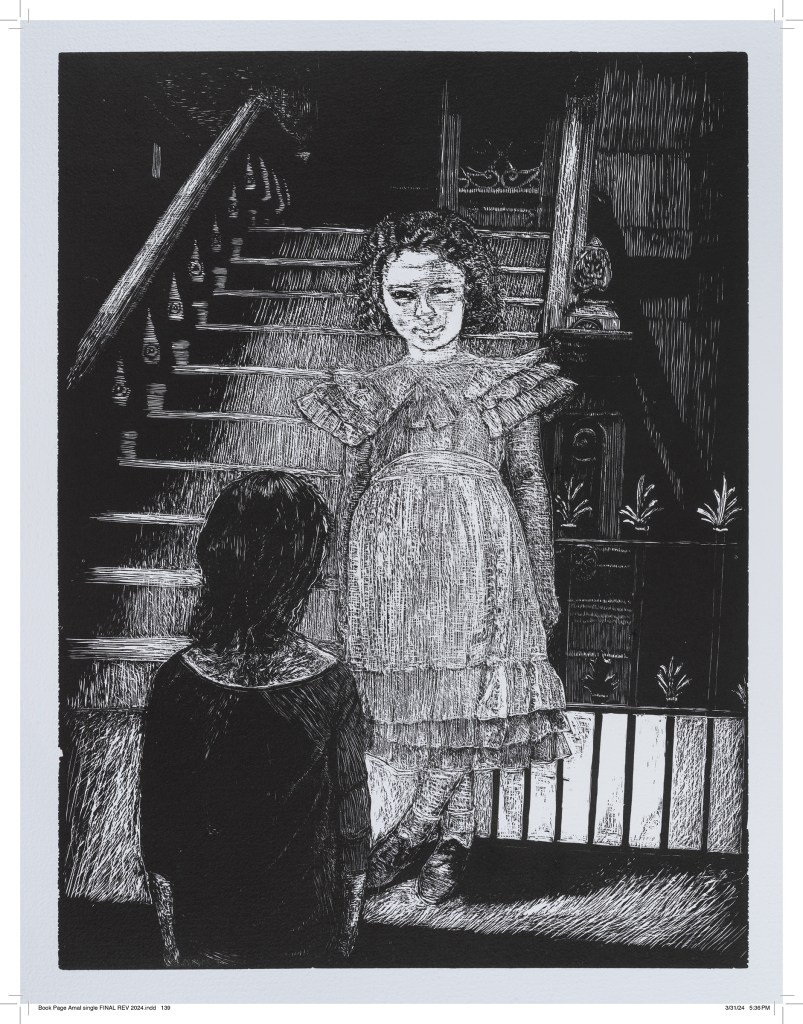

Several years ago, my cousin and I visited the brownstone on Putnam Avenue where my mother, his father, and our aunt grew up. The house looks much the same as it did when they were children. The cross street, which was called Sumner, is now Marcus Garvey Boulevard. As we stood in front of the house, I imagined my mother as a young girl descending the stairs.

The union was dissolved in 1976. New unions are emerging. The fight for a living wage continues.

What did the research process entail?

Books lent by my cousin, who taught labor history helped with early research, as did the New York Public Library’s picture collection, the Kheel Center at Cornell, family photo albums, a search of Ellis Island records, and later, online searches.

With a Cullman Center Fellowship for Scholars and Writers at the NYPL, research for Amalgam expanded in directions I hadn’t anticipated. A fellow in history directed me to books and documents, and a Soviet propaganda poster of a religious Jew wearing a yarmulke and cradling a pig. The Dorot Division added information about Jews in Russia. Elsewhere, at the library, there were books about Frances Perkins and Sidney Hillman, both of whom were responsible for humane legislation.

In the Map Division, there was a document that showed Poland’s changing occupiers over a few hundred years. Every day at the library, I passed a vitrine honoring Andrew Carnegie for the millions he had given to build libraries, while I simultaneously read about the massacre, years earlier, at his company, the Homestead Steel Mill, that his manager, Henry Clay Frick, had instigated, and which he approved. He was a man of great contradictions who grew to deeply regret these deaths. When they were old men who hadn’t spoken in 20 years, Carnegie sent Frick a letter asking to meet, and to let “bygones be bygones.” To which Frick replied, “You can tell Carnegie I’ll meet him. I’ll see him in hell where we are both going.” A new section about labor history was added to Amalgam, with other “Meetings in Hell.”

I love the way you’ve blended and contrasted different graphic/visual approaches. For instance, your line is looser than your editorial work. What was your thinking, doing the book in this manner?

These pieces began as small drawings that were blown up (as did most of my earlier editorial work). The drawn line that expresses both meaning and human feeling has always been my starting point—if that isn’t working, the time-consuming finish is just technique. Occasionally, I’ve cut faces out of the lino block and glued in replacement cuts that felt truer to the person. Some of the people are drawn more realistically, while the scribbly lines in others, sometimes within the same picture, describe the character. It’s not usually a conscious choice — the larger scale and self-imposed deadline probably allow for more attention to variation and experimentation.

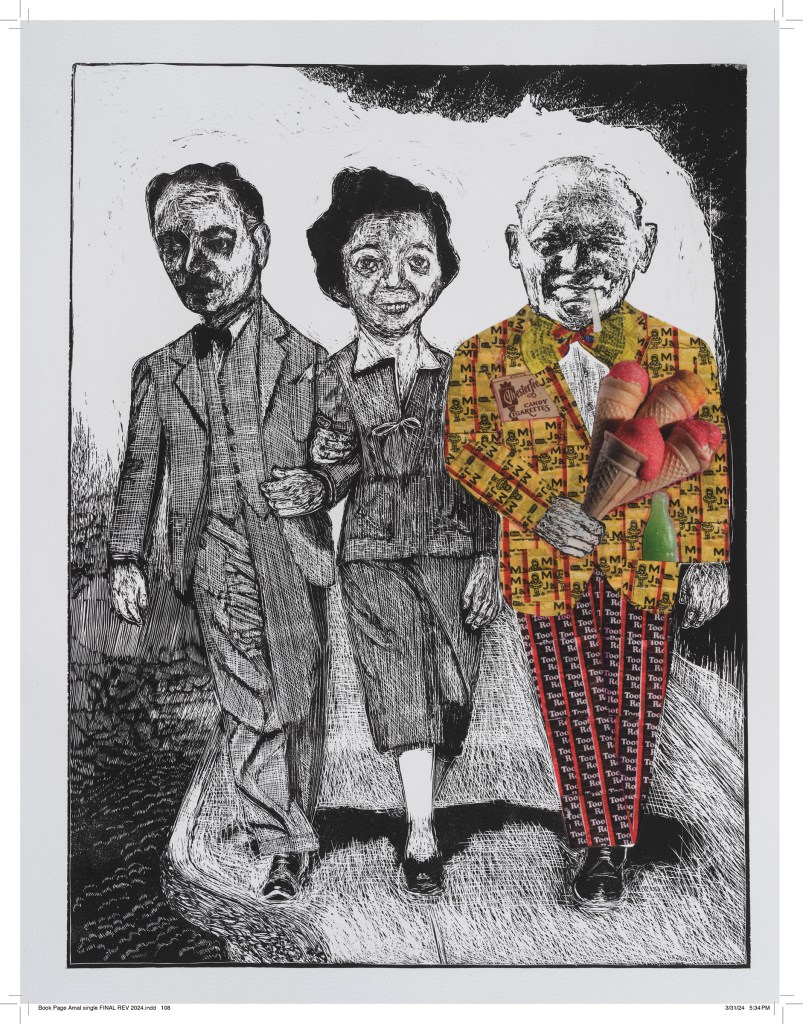

As far as different visual approaches, many with collage elements, without a deadline I had time to pick out Zabar’s most beautiful challah that became my grandmother’s many-breasted torso. And to get vintage candy from Economy Candy for the outfit of an uncle who owned a candy store underneath the EL on Kings Highway.

An actual girdle that had belonged to someone in the family (it was a relief not to have to buy one on eBay) became the bungalow where my grandfather had packed in so many of us.

I am also impressed by the design of the book. It falls into the graphic novel/memoir genre, but it goes beyond the conventions. What was your intention in avoiding the comic strip format?

This book is a hybrid, with both single-page images, several running overspreads, and others composed of multiple parts. My only considerations were whatever made sense for a particular part of the story, along with how everything would work together. I’d initially thought of this book as an artist’s book, a concertina with attached small accordion fold books in a numbered edition of 15. But it became increasingly important to me to have Amalgam out in the world- published as a graphic non-fiction. And I’m extremely excited that it was produced with a foldout that gives the book so much added meaning.

What is the significance of the keyhole (and other metal door parts)?

Doors, and their parts — hinges and keyholes — reoccur throughout Amalgam. The gilding on the cover’s Golden Door is wearing away. Parts are rusty. The peephole is ominous. Walt Whitman said, “Unscrew the locks from the doors. Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs,” which meant quite a different thing to my grandfather. With always open doors in the 4-family house, three generations were hinged to each other.

Everyone could look inside everyone else’s life as if people were composed of keyholes.

Factory workers were Locked Out and Locked In, disastrously. The book ends with my grandfather’s departure, outside a small screen door.

Was there any part of the actual history that you left out? Or left to the imagination?

The foreman’s son, who worked in the factory stole war relief funds, probably to pay his gambling debts. He was found out, escaped by joining the army, and was killed in the war. He left behind his wife and child, along with his father. With so many tragic stories about wartime, I don’t know why I find this one so haunting.

(Unions contributed donations to the war effort that were sometimes deducted from paychecks. But there was no clear image to work with and nothing I could find to document this.)

I never completed a story about my mother and her friend Pauline’s visits to the USO in New York City. They would go there to talk and dance with soldiers. Pauline would always remove her wedding ring. My lovely mother was not chosen to be a USO hostess. I couldn’t find photos of the interior of the NYC USO to flesh this out, despite the wonderful title at the library, a book called Good Girls, Good Food, Good Fun.

What would you like the reader to take away from this story?

Someone once remarked about this book’s focus on an “ordinary” person. I never thought that my grandfather was ordinary despite a lack of fame. He believed in something truly extraordinary: fairness in an unfair world, and he fought a good fight.

When I first told my beloved mother (who, contrary to everyone’s opinion was occasionally not sweet) about what I was working on, she had said, “Who’s going to be interested in our family?” After which she added, somewhat more kindly, “But I was wrong about the other one” (artist’s book on torture.) I hope that she would have liked this book.

A woman wrote to me that the depiction of my grandfather conjured up her father’s character (although my grandfather was employed by Howard Clothes and her father by the World Health Organization).

So I guess that is what I would like someone to take away, that in the images of this very specific family, they could recognize their own.